Introduction

The arrival of Europeans in the Americas was an event that would irrevocably change the course of history of mankind. By the time the first explorers had landed, an invasion of the continent had already become inevitable. For sixteenth century Europeans, South America became a screen onto which they could project their fantasies of discovering a new Eden. Many of them lost their lives in pursuit of this illusion, while many Native Americans lost theirs in a struggle to defend their way of life. One man’s dream is another man’s nightmare.

–

In the early twentieth century, the accidental arrival of a species of ant in Europe drastically modified the coastal environment of the European Mediterranean. Shiploads of Argentinean grain, sugar and wood exported to Europe brought with them the species Linepithema Humile, also known as the Argentine ant. This ant is notorious not only for its exceptional reproductive capacity, but also as an invader that kills and enslaves other native species. From Genoa to the Atlantic coast of Portugal, a stretch of nearly 5,600 kilometres along the Mediterranean coast, there exists a so-called “super-colony” of the Argentine ant.

Crossfade, c-print A4 – Mario Asef © 2012

.

The Individuals

Since the middle ages Europeans apparently developed a certain “shock and awe” war strategy: an astonishing brutal attack in order to break down the fight spirit of the opponent. The “Hun Speech” of Wilhelm II for example, addressed to the German troops led to the violent suppression of the Boxer rebellion in China in 1900 with the purpose of clearing the way for the German culture once and for all: “No quarter will be given! No prisoners will be taken!“

–

The Argentine ants are very aggressive and due to their quantity take other ant species without difficulty, even ants that are much larger. Argentine ants are unremorseful and brutally attack their adversaries until the enemy colony is destroyed. Even a nest of killer bees would probably not be able to counter against an invasion of Argentine ants. They also attack bird nests, driving off the mother bird and killing the young.

Crossfade, c-print-collage A4 – Mario Asef © 2012

.

Changing the Social Organisation

In the early phase of the invasion of South America the Europeans were friendly and cooperative to each other. But as soon as the continent was under control, the different European nationalities started to fight each other. Since the nineteenth century national associations of immigrants in Argentina strained to soften the process of adjustment. Different European communities such as the Basques, Catalans, Italians and French united in mutual aid societies and groups. The new ideas that came with the migrants from Europe led to the rise of the labour movement and allowed for the emergence of anarchism, socialism and syndicalism.

–

While Argentine ants from rival nests normally fight each other to death in their original habitat, Argentine ants from the super colony in Europe have the ability to recognize each other and to cooperate even if they come from nests at opposite ends of the colony’s range.

The Linepithema Humile is a polygynous and polydomous species which means that one colony can have more than one queen and several habitats. And so, when workers from different colonies meet they do not treat each other as rivals which provides the Argentine ants an evolutionary advantage over other ant species.

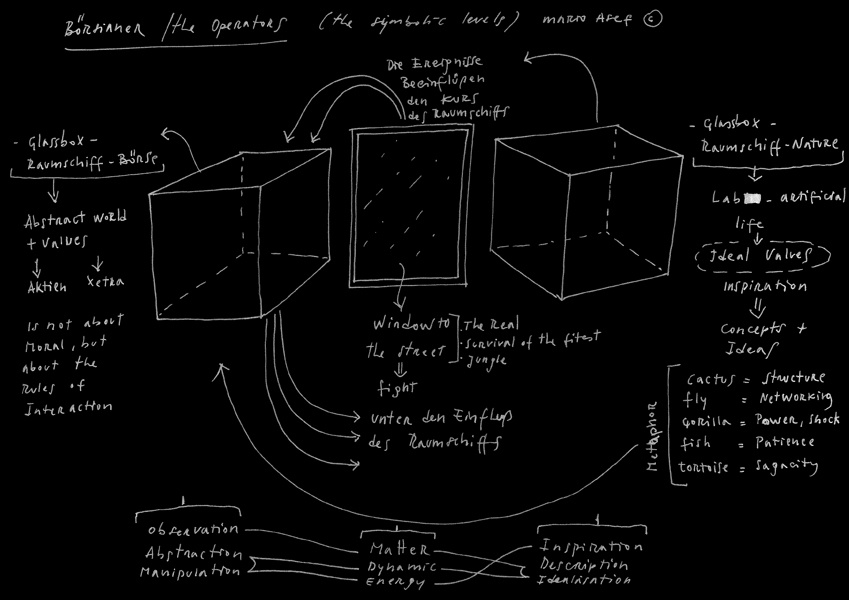

Crossfade, drawing A4 – Mario Asef © 2012

.

The Social Stomach

(Mate)

This drink is made from infused dried leaves of yerba mate (holly Ilex paraguariensis). The term “mate” originally referred to the drinking bowl (from the Quechuan term mati, bottle gourd), but is today used for the drink itself. Drinking mate is traditionally a social event around La Plata River. It is served with a metal straw (bombilla). When mate is drunk in a group, the same bombilla is travelling from mouth to mouth. Mate is offered to every visitor, traveller or friend as a welcoming gesture. Drinking mate is a communicative practice which offers an exchange of information among the participants.

–

(Crop)

An Argentine ant has more than one stomach. One stomach is for itself, while the other is the crop that is used to feed others. With their mouths pressed together the ants feed each other. The food comes out of one ant‘s crop and into the other ant‘s mouth. Pheromones come with the food and are exchanged as well. They keep information on needs, excitement or danger. Pheromones can also create a bond or friendship between colony members, helping them to work together.

Crossfade, drawing A4 – Mario Asef © 2012

.

Impact on the Environment

The death of millions of indigenous people during the years of the colonization of South America and further periods of European invasion was not caused alone by physical violence. The massive death rate, which decreased the indigenous population by 90 percent, was also due to diseases like influenza and chicken pox, which came with the invaders. In addition to this, slavery was another important aspect of the high native death rate, where indigenous people died because of bad nutrition and hard labour.

–

The Argentine ants have made a severe impact on Europe’s ecosystems. They have conquered and monopolized the land of South European ant species because of their social rules: The Argentine ants drive out or kill the native ants of a newly invaded territory and steal seeds from their beds. As noted by Laurent Keller of the University of Lausanne, Switzerland: “Cooperation allows the colonies to develop a much higher density than that which would normally occur, eliminating some 90 percent of other types of ants that live near them”.

Crossfade, c-print-collage A4 – Mario Asef © 2012

.

Conclusion

Human migration is often caused by extreme conditions. Migration is used as a strategy to survive or to obtain a better quality of life. This is the reason why people from areas with lower resources and higher competition emigrate to areas with higher level of resources. The majority of immigrants in Argentina came from Europe, mostly from Spain and Italy but with a substantial influx of British and Germans. Also notable are Jewish immigrants escaping persecution. The total population of Argentina rose from 4 million in 1895 to 7.9 million in 1914, and to 15.8 million in 1947.

–

The extreme domination of certain species within an ecosystem shows clear evidence of a system out of balance. The Argentine ant marked the ecosystem of the European Mediterranean coast to such a degree that the notion of that Area without Argentine ants influence will be inconceivable in the future. It is men who probably created the ant mega-colony by transporting the insects around the world and by continually introducing ants from three continents to each other, ensuring that the mega-colony continues to grow.

Crossfade, drawing A4 – Mario Asef © 2012